2024’s been a banner year for author Frederick Luis Aldama. In addition to the publication of his YA novel (in English and Spanish) and the graphic novel, Through Fences, he also published his climate sci-fi, Labyrinths Borne (illustrated by JItzel). Set in the not-so-distant future when the planet’s climate patterns are upside down and a mysterious disease dissolves the bones of adults, the planet’s future lies in the hands of the surviving youth.

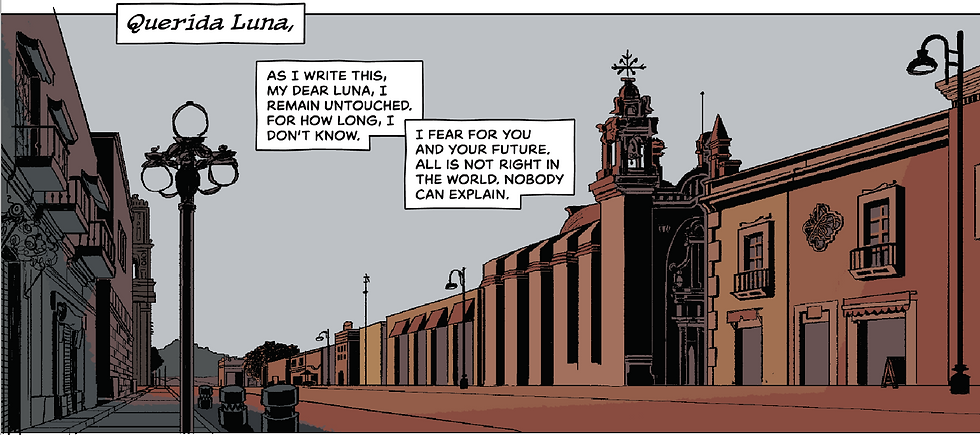

At the core of Aldama’s story is the profound intellectual and emotional bond between young Luna “Cassie” Casandra Coatlicue and Papá, a brilliant writer and thinker desperately clinging to his final days. Through a series of letters and journal entries, we discover how Cassie and other youth, living in a bunker at the edge of the world, use science, philosophy, literature, and the arts to find a sustainable way forward for life on earth.

With Labyrinths Borne, Aldama joins an extraordinary list of BIPOC authors creating and innovating within the sci-f/cli-fi narrative space of speculative today. I think readily of Giannina Braschi, Carmen María Machado, Junot Díaz, Nalo Hopkins, David Bowles, Ted Chiang, Alexander Chee, Octavio Butler, Nana Ekua Brew-Hammond, Hasnathika Sirisena, SL Huang, Rosaura Sánchez and Beatrice Pita, Daniel José Older, N. K. Jemisin, Nisi Shawl, Charles Yu, Fernando A. Flores, Waubgeshig Rice, Silvia Moreno-Garcia, Rebecca Roanhorse, Malka Older, and Zoraida Cordoba, among others. And, like these authors, Aldama builds a storyworld that looks to what we can learn from the past, to make a better present, and imagine a better future.

I had the opportunity to talk with Frederick Luis Aldama about Labyrinths Borne. Along the way we talked about science fiction, Latinx representation, learning from the past as well as the importance of hope, solitude, and slowing down and taking pause for self-reflection and creativity to happen in an otherwise fast-paced, social media hyped up world.

Ana Paula Cardenas: With Labyrinths Borne you emphasize the importance of bringing humanities, literature, and the arts into science and technology to create a sustainable future.

Frederick Luis Aldama: Mainstream sci-fi is singularly obsessed with building storyworlds filled with sparkly, new technology. It’s also obsessed with finding militaristic solutions to its problems.

I wanted to conceive of the future in a radically different way. Yes, it’s a future where we’ve basically brought the planet to the edge of death: black ice appears in the summer and the bones melt of anyone older than 25.

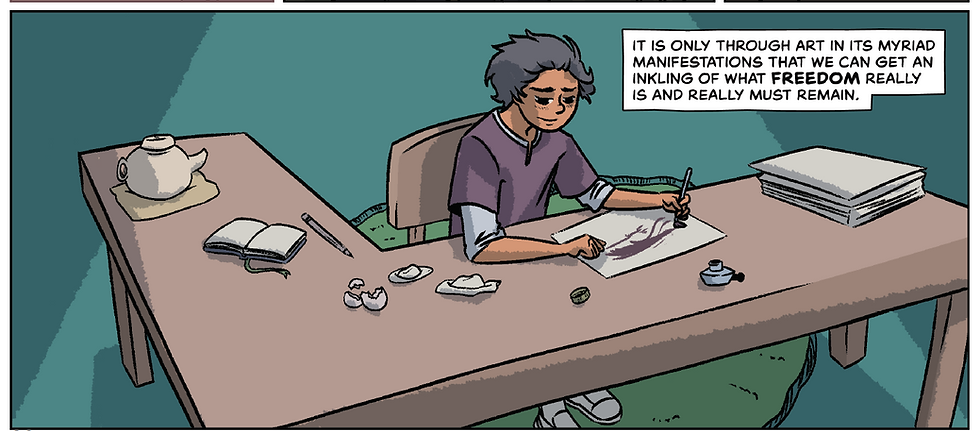

But I wanted to offer another, more hopeful view of the future. One where the new gens look to philosophy, literature, art and science and technology to build the world anew. It’s metaphysics and art that helps this new gen ask new questions, see the world from a new perspective, and find sustainable, progressive solutions—and not actions and knee-jerk reactions that result in death and destruction.

The sine quo non in STEAM is the Art. Without storytelling, philosophy, and art—without the story’s invitation for others to co-create—technology and science self-suffocate.

APC: Is this an example of the storytelling science that you talk about in your classroom and work?

FLA: Indeed, it is, Ana. It takes a lot to grow and exercise new storytelling muscles, if you will. When everything we’re fed repeats again and again the same plot and characterization in its speculative storyworld building, it takes work to figure out how to step off this hamster mill and do something new. That’s what storytelling science is all about. It’s about understanding the conventions of story by dismantling them, then doing the work to rebuild them in ways that take us into new storyworlds and new territories.

It takes a lot to grow and exercise new storytelling muscles

APC: Along with celebrating creativity, Labyrinths Borne also celebrates our capacity to hope.

FLA: At a certain moment Cassie and her peers put on a performance of Homer’s The Odyssey. Among the many themes highlighted include creativity and invention (the shaping of a nuptial bed wood from tree branches) as well as hope. Penelope’s hope that Odysseus will return. Odysseus’s hope that he will make it back to Penelope.

APC: Along with hope, you infuse Labyrinths Borne with joy. The joy between Papá and Cassie, and also the joy of the new gens working together to rebuild their world.

FLA: It’s a hope and joy that stands in contradistinction to the dark emotions that feed xenophobia, homophobia, misogyny; those negative feelings fed by the fear and anger that we see ripping the world apart today. There's a moment when Papá writes, “humanity began to end when people backed political authoritarianism and ideologues ideology of nationalism. It ended when a pandemic of fear led a majority of people on the planet to delight in inflicting suffering on the unwelcome disposable women, children, ethnic and racial, others bisexual, trans, gay, lesbian peoples.”

APC: There’s also a moment when Papá writes how if you kill the person and you kill the hope, you spread the fear—a collective fear.

FLA: Hope is the emotion that pushes hard against fear—all those negative emotions that try to crush our dreams. Hope allows us to transcend fear—and transcend the present, opening us to new ways to imagine a better life and a better future for all.

APC: Is hope the same as faith?

FLA: Faith and fate go hand in hand; it’s the core to religions; it is inaction; it is believing in something to come that will save the day—and not seeing clearly that we as a collective have the power to act and actively work to make life better, for everyone.

APC: The relationship between Papá and Cassie is at the heart of Labyrinths Borne, and with this a celebration of Latinx culture and familia. We don’t see much of this in mainstream media.

FLA: I chose to geographically separate Papá and Cassie. Their bond—the heart of their relationship—is experienced by you, the reader, as you move from Cassie’s journal entries to Papá’s letters. So, while we know that he will never read her journal and she will never receive his letters, there’s a powerful bond between the two as they ask questions of one another and share insights about what they are reading, thinking, and doing. This is where we feel the cariños that typifies Latinx familia and community life, and that we don’t see much of in mainstream media.

APC: We mostly see representations that portray Latinos as criminals, buffoons, hot-tempered, and hypersexualized. It’s also why I found your children’s book, Con Papá so compelling and important. You bring to life the tenderness and care that’s the life blood of Latinx familia.

FLA: Gosh, I’m glad you brought up Con Papá. Whenever I’d go to the library with my daughter, I’d never find any tender, affectionate books about Latino dads and kids. Teaching them languages and how to read, cook, sew, dance, swim, and ride a bike. How to “unzip the sky,” as the last line of the book reads.

APC: Papá in Labyrinths Borne is super smart and exudes tenderness and affection.

FLA: We need these stories—these antidotes to constant barrage of images of us as Latinx papás as only “bad hombres.”

APC: You chose to set Labryinths Borne deep in Mexico (Papá’s pueblo) and on the Mexico side of the US/Mexican Border (Cassie and her peers)?

FLA: So much mainstream cli-fi (climate fiction) and sci-fi is set in LA or New York City. It’s coastal and US centric. It’s as if the future doesn’t exist for those outside of these US metropolitan centers.

Of course, the future will unfold in the peripheries, it’s just that Hollywood and the publishing industrial complex don’t see us in the future. Labryinths Borne puts the beauty of places like Puebla, Mexico, front and center in the future. It reframes what many mistakenly view, courtesy of the media industrial complex, as the desert wasteland of the U.S./Mexico borderlands as a source of creativity and nourishment capable of revitalizing the planet.

Labryinths Borne puts the beauty of places like Puebla, Mexico, front and center in the future.

APC: Cassie and Papá connect through their shared love of learning. It’s Papá’s legacy to Cassie. Does this spring from your work as a professor?

FLA: Papá reminds readers of the importance of the learning and passing down of knowledge; of learning across different disciplines in ways that lead to the convergence and emergence of new knowledge; of the importance, too, of new generations like yourself questioning, revising, and building new knowledge systems.

The learning that Papá shares with Cassie before they are separated by "The Event" provides the foundation for her to read critically and creatively all the books she has on hand in the sanctuary and as part of the collective project to reboot the planet known as Labyrinths Borne. It helps Cassie and her peers figure out how to create better solar technologies and sustainable agriculture. It’s the anchor that allows her to learn and practice what she learns, and in doing the learning, revise knowledge systems. It’s a celebration of learning—and learning by doing. It's Labyrinths Borne.

APC: Papá's reflections are so incisive, including his championing of the slow engagement with life.

FLA: We all know that as we age, we have more experiences and more to reflect on. We think more before we leap, so to speak. And this in everything we do. There’s less urgency, and more a relishing in the slowness of the flow of life: Slow reading. Slow viewing. Slow listening. Slow learning. Slow attentiveness to the world. It's learning to take pause and carefully open to the world with all our senses.

APC: I really appreciate this. There’s so much distraction thrown at us, it’s hard to slow down, take pause, and attend in a very focused way.

FLA: And more than ever we need that deep focus if we are going to do more than act superficially in the world. If we are going to push through to new ways of imagining and creating new pathways into a sustainable, progressive future.

APC: Papá also embraces his solitude, something also lost today with the onslaught of social media and the push for us to busy ourselves all the time.

FLA: This takes us back to earlier in our conversation, Ana, when we talked about fear. The mainstream wants us to think solitude is wrong; to fear solitude. Yet, we need this in order to self-reflect; to create; to ultimately reengage with others in positive ways. So, Papá embraces his solitude, but not in a narcissistic way. In a way that is ultimately creatively social and socially creative.

APC: Papá reminded me that it’s okay to be bored. With the kids I babysit, it’s when they are bored that they are most creative; when they learn to enjoy being with themselves, and no longer rely on something external to themselves to make them happy.

FLA: Absolutely! Boredom rocks. It’s that pause that demands that we become at ease with ourselves. It’s that pause that can open new ways of understanding ourselves and the world.

APC: Papá writes about how memories of one’s past are like visiting a different country. For me, this resonated especially with how immersing oneself in a vastly different culture forces us to really grow in the present and in ways that can enrich our future.

FLA: When we delve into the past, we experience that sense of newness we get when visiting a completely different country or culture. New customs, languages, sights, smells, ways of touching and interacting, all pull us out of our habituated states. It’s like being a child again when your brain is on a constant blitz, growing thousands of new synaptic pathways. Traveling to another country can make new our sense of self in the world. It can open our eyes to see new pathways into the future.

APC: But can the past also be a burden, in the sense of traditions that might be harmful to oneself and others?

FLA: Absolutely! The past can be used to oppress—and exploit. But if we take the view that we can learn from the past and learn deeply from revisits and visits to a complex past, then we can creatively innovate our present.

Let me add, too, that I’m not proposing a touristic idea of learning from visiting other countries. That visiting Mexico today is somehow visiting the world in a distant, frozen past. This gets us off track. Mexico-as-other country is constantly influx. It's changing constantly. Even just a month or so ago when I was walking in Roma Sur I heard and saw this impromptu mariachi hip-hop performance. It still took me out of myself. It was Mexico City alive, breathing, changing.

APC: Any last words?

FLA: I hope Labyrinths Borne shows the world how this storytelling capacity of ours can allow us to imagine better ways for us to travel eyes-wide-open into a living, breathing past in ways that help us find ourselves in the present, and that can open ways of new thinking, feeling, and doing in a new, remarkable future.

APC: Congratulations. It's a beautiful graphic novel.

FLA: Gracias!

ความคิดเห็น