Melissa Castillo Planas Reviews Magical / Realism: Essays on Music, Memory, Fantasy and Borders

- Melissa Castillo Planas

- May 3, 2024

- 8 min read

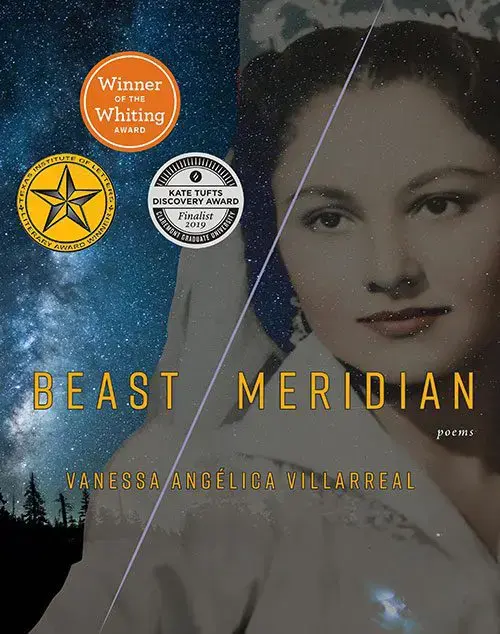

When I recently taught a course on contemporary Latinx poetry at Lehman College, CUNY, I immediately reached for Vanessa Angélica Villarreal’s collection Beast Meridian (Noemi Press, 2017). Beast Meridian, which received a Whiting Award, a Kate Tufts Discovery Award nomination, and the Texas Institute of Letters John A. Robertson Award, combines decolonial and borderland theoretical inspired imagery to braid together poems that subvert ideas of nation state, identity, gender and more. Before recalling a childhood in Texas as the daughter of immigrant parents, she opens the collection with a persona poem, “Malinche,” the text laid out to create an empty box in the center of the poem, a gap or whole, perhaps. Rather than

addressing gendered narratives about La Malinche’s “betrayal,” Villarreal centers action and desire writing, “I hunt the wilderness in myself stalk the tall grasses I am / she who betrays blood for a little bit of kingdom” (15).

My students, the majority of them Latinx, were immediately drawn to poems like “Assimilation progress report” (36) and “Gulf Pines, or Final Assimilation Room” (37) that address the psychological trauma of pressures to conform to whiteness and the aftereffects of a continual “civilizing” project meant to subdue and control. In later poems, like “Malinalli” (believed to be the true name of La Malinche), Villarreal invokes a powerful voice of female resistance while also imagining a different future: “I bride the rivers across time / & find our people & steal back our/ riches hide among deer disappear into/ the forest where reunited we will spill/ & spill & spill spread like a flood” (70). All of this, a long-winded way to say, Villarreal is a fantastic poet. I came into this review as a fan of her work.

However, if Beast Meridian is thought-provoking, Villarreal’s soon to be released collection of essays, Magical / Realism: Essays on Music, Memory, Fantasy and Borders (Tiny Reparation Books, May 2024) is a revelation. In the 16 essays, 10 shorter interludes, and an afterword, she analyzes key moments in her life and her family history via TV shows, movies, music, literature, theorists, philosophers and more.

In the tradition of Roxane Gay’s work, who’s essays in Hunger are about her own experience with sexual violence and relationship with weight as well as societal narratives about these topics, or Carmen Maria Machado’s In the Dream House, which centers her same-sex abusive relationship alongside mainstream media and society’s views on lesbian couples while employing the metaphor and theory of fairytales, Villarreal’s essays reach far beyond her own life. Instead, the anecdotes from her childhood, reflections on her divorce and other traumatic experiences, and attempts to learn and understand her family history, serve as a vehicle to explore historically rooted issues of violence, toxic masculinity, gender norms, racism, anti-immigrant prejudice, monogamy, mental health, female and colonial erasure, white supremacy, AI, racial capitalism, and more in a way that is exciting and surprising due to the unique mix of theory and popular culture.

The anecdotes from her childhood, reflections on her divorce and other traumatic experiences, and attempts to learn and understand her family history, serve as a vehicle to explore historically rooted issues of violence, toxic masculinity, gender norms, racism, anti-immigrant prejudice. . .

The opening chapter, “The Migrants Journey,” is a list of themes, provocations, theory, family stories, and questions that animate the memoir. Building on some of the themes of Beast Meridian, Villarreal dives into the literary and national narratives and genres that effect migrant and first generation lives. She writes, “I erased the problems, the color, the wildness and created the buen hija they could be proud of, living out of the grand narratives of what a ‘better life’ meant to them: assimilation to whiteness, cis-heteronormativity, bootstraps individualism, mestizaje, Manifest Destiny, and the earliest one little girls are taught to believe, Happily Ever After. “ (4)

Later interludes titled, “Encyclopedia of All the Daughters I Couldn’t Be” – further delve into these pressures with conversations, moments in childhood, and vivid dialogue that provide an anecdotal feel to balance some of the more theoretical driven essays. Later in this same first chapter, she brilliantly asks, “Are migrants on the hero’s journey?,” evoking Joseph Campbell’s famous scholarship in a way that also demonstrates its limitations. As Villarreal continues, “The American Dream is a fairy tale, after all. Migrants, like heroes, are forced to leave home, but their journey is not into the underworld—it’s to the overworld, the global north, into empire” (18). Thus, in Villarreal’s work, theory is not abstract. Instead, literary theory about narrative practice is brilliantly highlighted to demonstrate how it connects to her own life and family life, as well as how it doesn’t.

Villarreal deftly combines philosophers and theorists including Baudrillard, Said, Freud, Gramsci, Derrida, Anzaldúa, Heidegger, Bachelard; writers such as Lionel Shriver, Melissa Febo, Toni Morrison, Marcelo Hernandez Castillo, Bhanu Kapil, M. Nourbese Phillip, Sontag alongside cultural and pop culture touchstones, like the 1934 Mexican song “El Ropero”, the 1984 film The Neverending Story or the smash fantasy TV series, Game of Thrones.

The ability to move through these diverse sources alongside personal and familial histories is what truly makes this writing vibrant and special. Whether considering high theory or analyzing a video game, Villarreal over and over again brings a new and fresh perspective to the material, proving that “advanced theory isn’t hard, it’s just gatekept, and with the right frame and language, anyone can understand it” (277).

My favorite chapters were the ones that centered around popular culture, particularly Game of Thrones, which is the subject of the marvelous final chapter, “When We All Loved A Show About A Wall.” As a fellow Mexican American who also loved the show, this essay helped me understand the resonance of the show and in particular the character Jon Snow, who Villarreal provocatively states, “is accidentally the best Mexican American character ever written for television” (329). Since Jon Snow is white, I was speculative at first about this statement. However, Villarreal’s analysis of the context of the show’s release during Trump’s presidency and the absence of a Latinx perspectives on Game of Thrones, especially considering the importance of the wall in the series was fantastic and shifted my point of view.

It is these unexpected combinations and conclusions that make each of these essays worth study: her father’s attempt at a rock career and their relationship is also a way to talk about Los Tigres del Norte and Selena; while a first crush on a white boy gives her an opportunity to explore proximity to whiteness, domestic labor, and white-Latinx love stories in Hollywood, through Jennifer Lopez’s career.

Another chapter about her pregnancy and concerns about having a boy when “I have only ever known gender as a modality of violence” (209) and how women in her family have loved men “no matter how toxic or violent” (2010) is connected to Vicente Fernandez’s beloved song “Volver, Volver” and Beyonce’s album Lemonade. However, for me, one of the book’s biggest contributions is demonstrating not just the importance but the theoretical and imaginative possibilities of a Latinx perspective on fantasy and science fiction.

One of the book’s biggest contributions is demonstrating not just the importance but the theoretical and imaginative possibilities of a Latinx perspective on fantasy and science fiction.

In another eye-opening chapter, Villarreal analyzes the rise in popularity of “historical high fantasy in earthy medieval setting” both as a scholar with a critical eye and as a fan as she admits this genre, “might be my favorite genre of visual storytelling” (248). Exploring the video games Dragon Age: Inquisition – Trespasser DLC and Assassin’s Creed Valhalla as “an allegory for a race war at the brink of an apocalypse and extinction” (248), Villarreal demonstrates the problematic nature of these “Viking narratives” that actually “implies a deeper cultural desire: the return of white male dominance, free from colonial baggage or accountability” (265).

As Villarreal points out throughout the book, mainstream fantasy and science fiction is always told from a western narrative context, and more and more frequently centers storylines about dystopian futures and apocalypses from which white heroes must survive and save humanity. Why not instead, as Villarreal suggests, consider the perspectives of people (ie Black and Indigenous) who have already survived the apocalypse and their attempts to imagine different futures as well as contemplate why are these dystopian narratives about white survival so popular?

Throughout, Villarreal brings freshness and nuance to genres and topics that are both generally considered “Latinx” by a white mainstream (ie immigration, assimilation) and those that are not (fantasy, video games), demonstrating the myriad of ways the Latinx community engages with US popular culture. Echoing comedian and actress Cristela Alonzo’s memoir Music to My Ears (2019) in which popular culture is her lifeline and obsession growing up as the daughter of a single undocumented mother, Villarreal reflects on the idea that, “…if we love American music, films, and television enough, America may love us back” (30). As an adult, of course, Villarreal recognizes America will not love her back, but that does not detract from her engagement with cultural phenomenon.

Importantly, the title to this collection is not Magical Realism but Magical/ Realism, and through that distinction, Villarreal also gives a master class on the style of fiction known as magical realism, its significance and contribution, and why it’s frequent application to anything Latinx is inaccurate and lazy. Her explanations alone about how the term “Magical realist” has been used as a way to marginalize Latinx books, while also connecting the development of the style that is little used in contemporary writing today to US funded violence against Latin American leftist movements during and after the cold war, should be required reading in many introductory literature courses.

Villarreal also gives a master class on the style of fiction known as magical realism, its significance and contribution, and why its frequent application to anything Latinx is inaccurate and lazy.

Not only does Villarreal adeptly clarify many long-standing misconceptions, she demonstrates over and over why narratives, why language and why genre matters. Magical realism developed in Latin American during a particular time for a particular reason, meanwhile, fantasy has long been functioning in a western imagination in which the characters are almost entirely white, also for a reason. Villarreal clarifies: “Fantasy discovers the New World, whereas magical realism is the world invaded by violence. If fantasy is a literature of world-building, then magical realism is the literature that results from world-breaking” (39). Genre matters.

Villarreal, however, invites us into the realm of world-building. In reflecting on the silences and gaps of her own family history, in refusing to censor her writing, and in sharing trauma with honesty and vulnerability, Villarreal also wants to imagine something different. At the end of her first chapter she writes:

51. Once upon a time, I was tempted to write a legible Mexican American girlhood: kind-eyed grandmothers and cumbieros, immigration trauma, a poor childhood, assimilation and in-betweenness, broken-down pickup trucks and undocumented family members, a harrowing tale of survival and resilience, just enough authenticity to claim the identity while being respectable enough to join the middle class.

52. But these stories are not mine to tell. (20-21)

I for one am grateful. Instead, Villarreal gives us stories and essays that defy expectations about a Latinx memoir or collection of essays. This book is not a quick read, but rather essays to be studied, savored, re-read and discussed. You may end up having to re-watch a fantasy film or show as well. But it will be well worth the time.

Comments